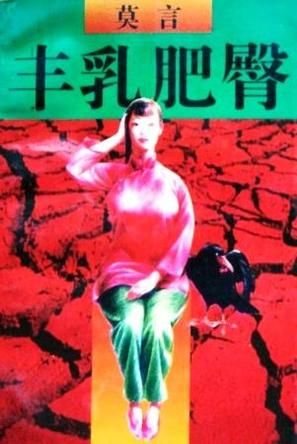

(By Luo Yanjie) Recent internet news has stated that the film adaption rights for Big Breast & Wide Hips, the work of 2012 Nobel laureate, Mo Yan, have sold for RMB 11,180,000 yuan, and the film will be directed by Zhang Yimou. Although Mo Yan’s agency ultimately confirmed that this was a false rumor, the cinematographic adaption of Mo Yan’s work has garnered public attention. With the trend of greater diversity in forms of work, we have seen more and more works recomposed in other artistic forms. Legally speaking, this re-composition actually belongs to adaption under the Copyright Law, and the work created is therefore adapted work. Today’s post will introduce the Chinese system for adaption of the film and cinematographic works.

(By Luo Yanjie) Recent internet news has stated that the film adaption rights for Big Breast & Wide Hips, the work of 2012 Nobel laureate, Mo Yan, have sold for RMB 11,180,000 yuan, and the film will be directed by Zhang Yimou. Although Mo Yan’s agency ultimately confirmed that this was a false rumor, the cinematographic adaption of Mo Yan’s work has garnered public attention. With the trend of greater diversity in forms of work, we have seen more and more works recomposed in other artistic forms. Legally speaking, this re-composition actually belongs to adaption under the Copyright Law, and the work created is therefore adapted work. Today’s post will introduce the Chinese system for adaption of the film and cinematographic works.

I. The adaption must be authorized by the rights holder of the original work

It must first be clarified that adaption refers to creation using the expression of others’ work as a basis but does not include the re-composition of others’ ideas. For example, rearranging a novel into live theatre. As the original dialogue or expression would inevitably be adopted, this would constitute the use of others’ work. Suppose however, only the story is used, but it is described using a completely different background or dialogue. In this situation, despite suspicion of being a knock off, because the protection from the Copyright Law only covers the expression, such an action could not be seen as an adaption and does not have to be approved in advance by the original rights holder.

In other words, at least two copyrights will be present in an adaption: 1) the copyright of the existing work and 2) the copyright coming from the adapted work. According to Article 10 of the Copyright Law, the right of adaption is a proprietary right. For this reason, in order to adapt a work, the adapter must gain authorization from the author.

II. The scope of use for adapted works must be recognized by the original work’s rights holder

But, according to Article 12 of the Copyright Law:

“Where a work is created by adaption, translation, annotation, or arrangement of a preexisting work, the copyright in the work thus created shall be enjoyed by the adapter, translator, annotator, or arranger”,

This does not, however, mean that an adapter can freely exercise the copyright of the adapted work. The main reason is that the adapted work may contain the copyright of the original work; therefore, when the rights holder for adaption excises its copyright, it will also exercise the original copyright. For this reason, the Copyright Law also stipulates that, “exercise of the copyright shall not damage the copyright of the original work.” So, the so-called “copyright” for adapted works more aptly refers to the right to stop unauthorized use of the adapted works.

III. Exceptions for cinematographic works

As previously discussed, in terms of exercising the right during and after adaption, the approval of the copyright holder is required. But, this does not apply to cinematographic work.

Although the Copyright Law regulates the right of filmmaking, in practice, cinematographic works will usually contain some level of adaption. Moreover, cinematographic works also include many other works, such as music. But, when Article 15 of the Copyright Law stipulates that “The copyright in a cinematographic work and any work created by an analogous method of film production shall be enjoyed by the producer of the work,” it does not resemble the above-mentioned clause in Article 12 that states that “exercise of the copyright shall not damage the copyright of the original work.” So, from the language of this article, it is clear that the exercise of rights for cinematographic work does not require permission of the prior rights holder.

Therefore, according to the Copyright Law, once the author of the original work has licensed the adaption of its work for a cinematographic work, the new work will not be restricted by the original work’s copyright once it is finished. No matter how the producer uses the cinematographic work, no license from the original right holder is required, even if the original rights holder has granted no rights in the licensing contract other than screening the cinematographic work.

Lawyer Contacts

You Yunting:86-21-52134918 youyunting@debund.com/yytbest@gmail.com

Disclaimer of Bridge IP Law Commentary

Short Link: